Ralph Nash was baptised Raphael Nash in the Catholic Church at Sologhead in County Limerick, Ireland, on the 12th June 1810. It should be noted that Ralph was an unusual name for the time. The current church of St Nicholas at Sologhead was built in the late 1800s but stands on the site of the earlier chapel in which Ralph was baptised. Ralph was the third child born to John Nash and Ellen Rogers; John and Ellen had four children together, Henry, Catherine, Ralph, and Margaret.

Sologhead (or Solohead as it is known today) was a rural area, 7km north-west of the large town of Tipperary, on the main road from Tipperary to the city of Limerick. Ralph’s parents, John and Ellen, were working-class Irish Catholics, and had no vote and no voice at that time. They may have had a small allotment of land which they rented; almost all allotments in the area were less than 50 acres and over 60% of them were 10 acres or less. The rents in county Tipperary were exorbitant; except for Dublin, they were the highest in Ireland. Tenants, regardless of their faith affiliation, were also required to pay tithes to the Church of Ireland (based upon the value of the land they rented); this was a huge point of issue with the Catholic Irish and part of the reason for much of the civil unrest in the country.

It’s difficult to say what sort of childhood Ralph would have had under these strained and difficult conditions. It’s unlikely that he attended school but there is evidence that Ralph had the opportunity to learn to read and write; it seems likely that this was a direct result of the apprenticeship in carpentry that he gained as a youth. As a carpenter Ralph was among the small minority of people in county Tipperary and Limerick who were not directly employed in agriculture. While this may seem a positive thing it was a more precarious situation. There were few industries in the cities and towns of Ireland and many of the alternative industries were service industries to agriculture, when agriculture was suffering a downturn, the supporting industries were in a worse situation.

By the time Ralph was 14 years old, Ireland was a powder keg waiting to explode. In the mid-1820s particularly (following widespread “disturbances” that saw the county of Tipperary, including Sologhead, placed under the Insurrection Act), it was recorded that there were several instances of tenants being required to pay rent and/or tithes to several different persons making a claim on the land which they were occupying. If they were unable to pay one of those persons, they were forcibly ejected from their land. The people were starving, barely surviving, and under constant threat of eviction and eventually they had had enough.

Ralph’s older brother and father may have been active in one of the secret organisations that were rising up around the countryside, fighting back against the inequitable treatment they were struggling under. These organisations were becoming increasingly militant and weaponised and the history of organised retaliation continued for many decades; today Sologhead is most infamously remembered as the site of the beginning of the Irish War of Independence when one of the secret organisations ambushed militia transporting weapons through the region on the 21st January 1919.

On the 16th August 1829, 19-year-old Ralph and his brother, 26-year-old Henry, stood before the court in Tipperary on trial for manslaughter. Authorities routinely used the courts to break the rural uprisings in Ireland – had Ralph and Henry been involved in a local uprising or protest action, and subsequently arrested for their involvement? Unfortunately, no details of their trial were found. Both men were convicted and sentenced to 7 years transportation to Botany Bay, New South Wales. Following their sentencing they were transferred to the prison hulk Surprise, moored in Cork Harbour. While conditions upon the hulk Surprise were said to be “cleanly, comfortable, and well superintended”, in truth, the conditions were torturous. The ship was not tethered to the shore, as other prison hulks in other ports were, and the prisoners were not used for labour during the day. The boredom alone would have been unbearable. It’s not surprising that several attempts were made to escape; at one time the ship was set on fire by prisoners and riots were not uncommon. What made matters worse, the prisoners were manacled at their ankles and wrists for almost the entirety of their time on board, resulting in painful ulcers and muscle cramps. Also common were the diseases of overcrowding, like tuberculosis (of the lungs) and scrofula (caused by the tuberculosis bacteria affecting the lymph nodes of the neck).

Ralph and his brother Henry were transported to Australia together on the convict ship Forth. Under the command of Captain James Oliphant Clunie, the brothers took their final glimpse of the coast of Ireland on the 1st January 1830 as they departed with 118 other convicts plus guards. The ship’s surgeon, William Clifford, remarked on the “extreme indolence” and the predisposition of the convicts to depression and illness; and little wonder given the conditions of their incarceration upon the hulk Surprise! Clifford’s remedy was to goad them into keeping busy about the ship; to what extent this helped, we aren’t sure. Sadly, three men died during the voyage to Australia, passing away from dysentery while still at sea.

Ideals about convict treatment and their purpose in the penal colonies across Australia had changed since convicts first arrived in Sydney Cove in 1788. Initially, convicts were considered a useful and productive part of building the new colony. Over time, as the numbers of free settlers and emancipated convicts grew, the feeling toward convicts changed and they were increasingly seen as the broken part of humanity, in need of painful and degrading “correction” as they served their sentence. By the time Ralph and Henry arrived in the colony, the prevailing aim of convict management was to disperse them away from heavily settled areas and assign them to landowners as cheap labour. Ralph and Henry had arrived in a colony that was a ‘world of pain’ for most convicts.

Upon reaching Botany Bay, Ralph and Henry were marched up the hill to the Hyde Park Barracks for their first muster in Sydney Cove. There they discovered that Henry, as a general labourer with no specific skills, was assigned to a free settler at Prospect, New South Wales; he was soon employed there as a farmhand or servant. Ralph as a qualified carpenter, however, had skills much desired in the developing colony and he was assigned as a ‘government convict’ and remained at Hyde Park Barracks.

The Barracks was not a prison, it was primarily a place to feed, house, and control convicts on government work assignments. By the time Ralph arrived, it was also the central place of administration and judgement/punishment for convicts in the colony. Monday through Friday convicts at Hyde Park Barracks attended to their work assignments, leaving through the main gates each morning, returning at lunch time, and again at the close of the day. Only convict chain gangs were guarded, all other convicts were expected to attend to their assignment without direct supervision. They were locked in the barracks at night but it was fairly common for convicts to jump the walls and go into the town looking for some ‘fun’; in theory, if they were discovered they were punished, but many of the constabulary could be bribed to turning a blind eye. Only the worst offenders, or repeat offenders, were shackled together in chain gangs. Interestingly, on Saturday the convicts were free to go into the settlement and seek work for their own profit; some did so, but just as many used the opportunity to frequent local saloons. For some of the convicts this opportunity to seek personal profit was vital for their survival. For all convicts housed at the Barracks, Sunday morning was spent at St James Church across the road from the Barracks, and Sunday afternoon could be spent at rest.

Estimates of up to 1300 men were housed in the Hyde Park Barracks during Ralph’s time. There were not enough hammocks for every man and as many men slept on the hard floorboards. Each ‘bed’ was made up with two government blankets marked with the broad arrow. These were not issued to the men but instead were assigned to the bed space and remained the property of the Barracks, punishment for stealing a blanket was harsh. Blankets were only washed twice a year; one can only imagine how stiff and smelly they must have gotten from dirt and sweat. Convict men were issued twice a year with ‘slops’, ill-fitting, one size fits all clothing consisting of two shirts, a jacket, a pair of trousers, and a pair of shoes. They had opportunity to wash these and their bodies once a week with their soap ration, but this was not enforced and the convicts were free to wash and bathe, or not, as little or as much as they wished. Another issue with the overcrowding was that the recreation hall was not large enough to house all the men, which wasn’t a problem as the court yard was spacious until there was rain and bad weather and many men were left standing shivering in the rain or huddled in a corner seeking shelter as best he could.

Writings from the period note that food rations at the Barracks were nutritious but they were insufficient for the number of men accommodated there. It was not uncommon for a convict to complain of hunger, so the Saturday to seek work for their own profit was vital to supplementing their limited diet at the Barracks. Breakfast consisted of a cornmeal porridge known as hominy. Convicts were evidently considered untrustworthy when it came to eating utensils and so their only implements were two paniers shared between a group of six men; no doubt fingers were the primary eating tools. A writer to The Monitor in 1826 noted: “The issues of corn meal without a spoon to use it with…present a scene as disgusting as it is degrading.” Is it any wonder then that a man, treated like an animal as the convicts were, from time to time lashed out in anger at those who deigned to treat him so poorly. When the convicts returned from their government work assignments for the midday meal it consisted of a greasy stew and bread so stale it was rock hard and impossible to eat. Again the want of a spoon must have been so degrading; though the hard bread may have been useful as a spoon if it could be broken in just the right way.

The convict assigned to a private individual had a chance, though definitely not always, of faring better than the convict on government assignment housed in the Hyde Park Barracks.

By 1832 Ralph was no longer only on government assignment and had at least two instances of being assigned to private individuals. From January to March 1832, he was assigned as a wheelwright to Sir John Jamieson of Regent Ville, near Penrith, New South Wales; it’s unlikely Ralph ever met Sir John personally. Sir John was a significant figure in the governance and development of the early colony. Profoundly interested in the development of agriculture in the colony he established the property he named Regentville as a model property with vineyards, and irrigation scheme, and even a woollen mill (1842) to discover and demonstrate what was possible in agriculture on Australian soil. By many the estate was considered highly successful. Sir John was an extravagant man but died in 1844 practically penniless following the collapse of the Bank of Australia in which he was the second major shareholder. His sons went on to become equally significant figures in the young colony. Life at Regentville would have been hard work for Ralph, and while it would have been something of a relief from the overcrowding of the Barracks, there seem to have been little to no opportunities for personal profit when on private assignment.

By the end of the year 1832 Ralph was assigned as a carpenter to John Wood, at Lowther (it’s not certain if this is Lowther in the City of Lithgow, or if there was a property by the name of Lowther closer to Sydney Town). Not much information can be found about John Wood, evidence suggests he may have been an emancipated convict who had been one of the earliest transported convicts to the colony.

It seems that Ralph was far from the model convict and by late 1834 he was working on a government road gang at Cox’s River. Cox’s River in the Hawkesbury-Nepean catchment area was the easiest point to cross the Blue Mountains into the great West. Sadly, on the evening of the 27th October 1834, Ralph, a man by the name of Doyle, and an unnamed watchman, were discovered missing at the evening muster (roll call) of the road gang. Ralph and an accomplice (assumed to be Doyle) violently entered a house on Cox’s River beating some of the occupants and making off with a significant quantity of goods to the value of £20. Though masked, Ralph was positively identified by witnesses, Doyle was not. The jury declared Ralph guilty of burglary, and he was sentenced to death. His record of gaol entry is so erroneous we can only assume that in frustration and anger Ralph gave a false report of his identity; the record stated that he was a protestant from Bristol who was a hatter by trade, was he trying to be blackly ironic?

Thankfully for Ralph his death sentence was commuted to transportation to Norfolk Island for life. Norfolk Island penal colony was one of the toughest penal settlements at that time and generally reserved for the hardest of criminals.

Norfolk was on the surface a picture of paradise, but in 1825 it was reopened as a penal settlement for the express purpose of severely punishing those convicts who reoffended while serving sentences of transportation in Australia or for convicts from England who committed particularly heinous crimes. It was intended to house the hardest of convicts and by 1835 when Ralph arrived, the gaol held between 1400 and 1500 convicts.

Uprisings and escape attempts were all too common, with the largest uprising occurring a few months before Ralph arrived. When Ralph arrived at Norfolk, the newly appointed commandant of the penal settlement, Major Anderson, had started a building program that would see significant infrastructure improvements on the island. Was Ralph’s death sentence commuted so that his trade skills could be utilised in Anderson’s building program? While it seems that Anderson had some ideals of the humanity of the convict and it was not unusual for him to seek pardons for certain convicts or to happily employ newly emancipated convicts he had known on Norfolk in his private ventures on the mainland, for most convicts Norfolk Island continued to be a place of horror and brutality under his governance. While reports are that military men and convicts were reasonably respectful of Anderson, he was considered a petty tyrant by civil servants employed on the island. Many of them left their posts well before their time was due and there was great call for Anderson to return to the mainland and answer to allegations against him.

Following Anderson’s recall from Norfolk, Captain Alexander Maconochie took up the post of Governor/Commandant of Norfolk Island. Maconochie was a deeply religious man who was convinced of the dignity of man, every man. He was a known prison reformer, and he was given opportunity to undertake prison reforms with the English convicts who had been sent to the Island; initially at least, he was not allowed to enact the same reforms with the convicts sent from the colony. In essence his reforms were centred around the ideals that cruelty debases the victim and society and punishment should be limited to reforming the convict to normal social and moral rules, and that imprisonment should have purpose rather than time, i.e. that a convict’s sentence length depends on the completion of a measurable amount of labour. He maintained a system of marks, where the convict attained greater freedom and responsibility as they proved themselves at each level. Unfortunately, Maconochie’s reforms were not appreciated by the wider community who believed that Norfolk Island should remain a place of horror for those it considered ‘lost causes’ worthy only of the harshest and most brutal treatment. Though he was recalled from office in just 4 years, 1400 convicts were discharged during under his reforms. Ralph had been returned to Sydney Town by 1845, and it seems reasonable to believe that he was one of the convicts given an opportunity to reduce his sentence through Maconochie’s reforms.

Not long after Ralph had been transported to Norfolk his brother Henry received his certificate of freedom, having served the 7 years transportation sentence the brothers had received in Tipperary. It’s unlikely that Ralph would have been aware of where Henry was at that time, and even if his illiterate brother could have found someone to read letters from him, Ralph would not have been permitted or even had the means to stay connected with his brother. As Henry was enjoying his new freedom Ralph had no prospect of ever being released from prison.

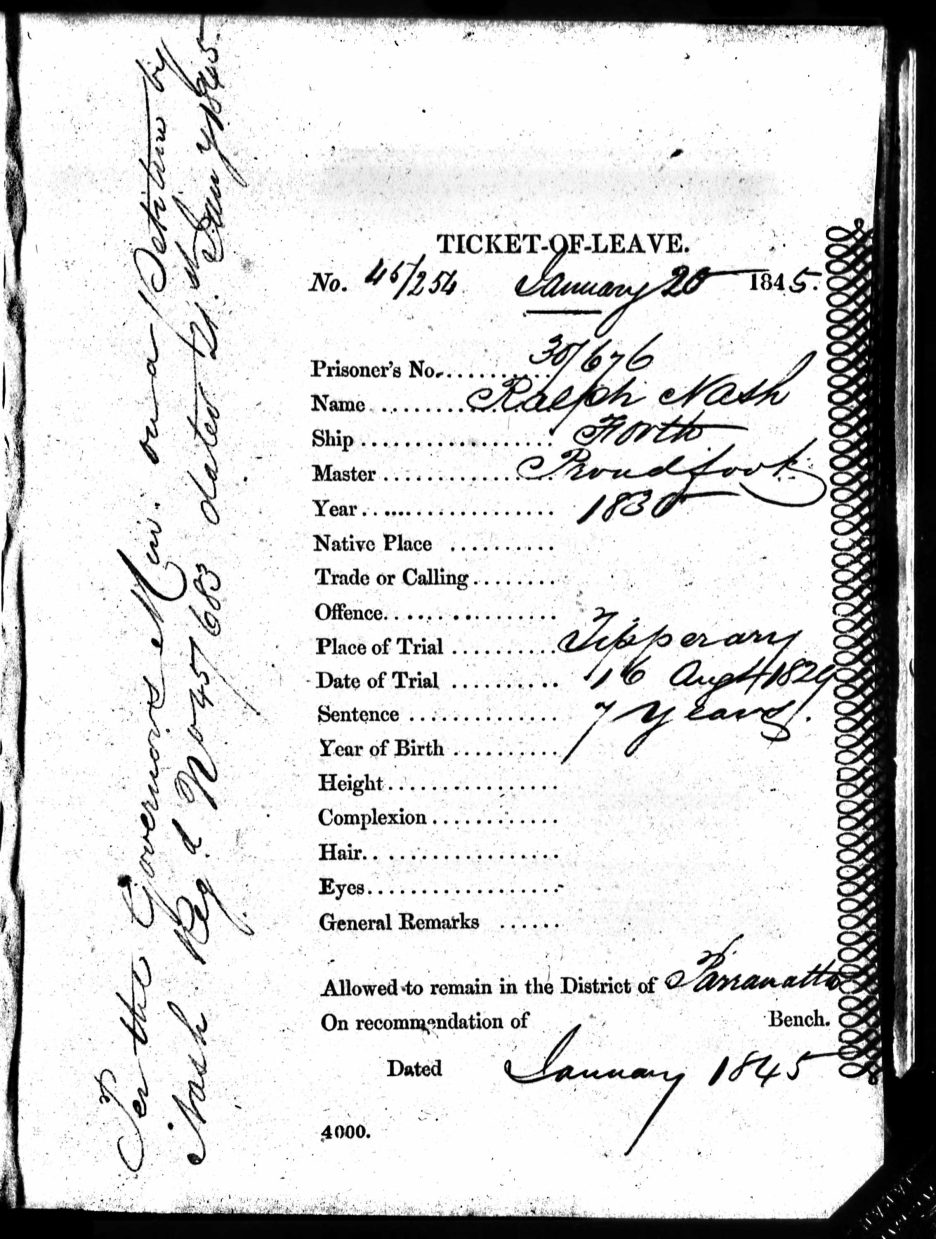

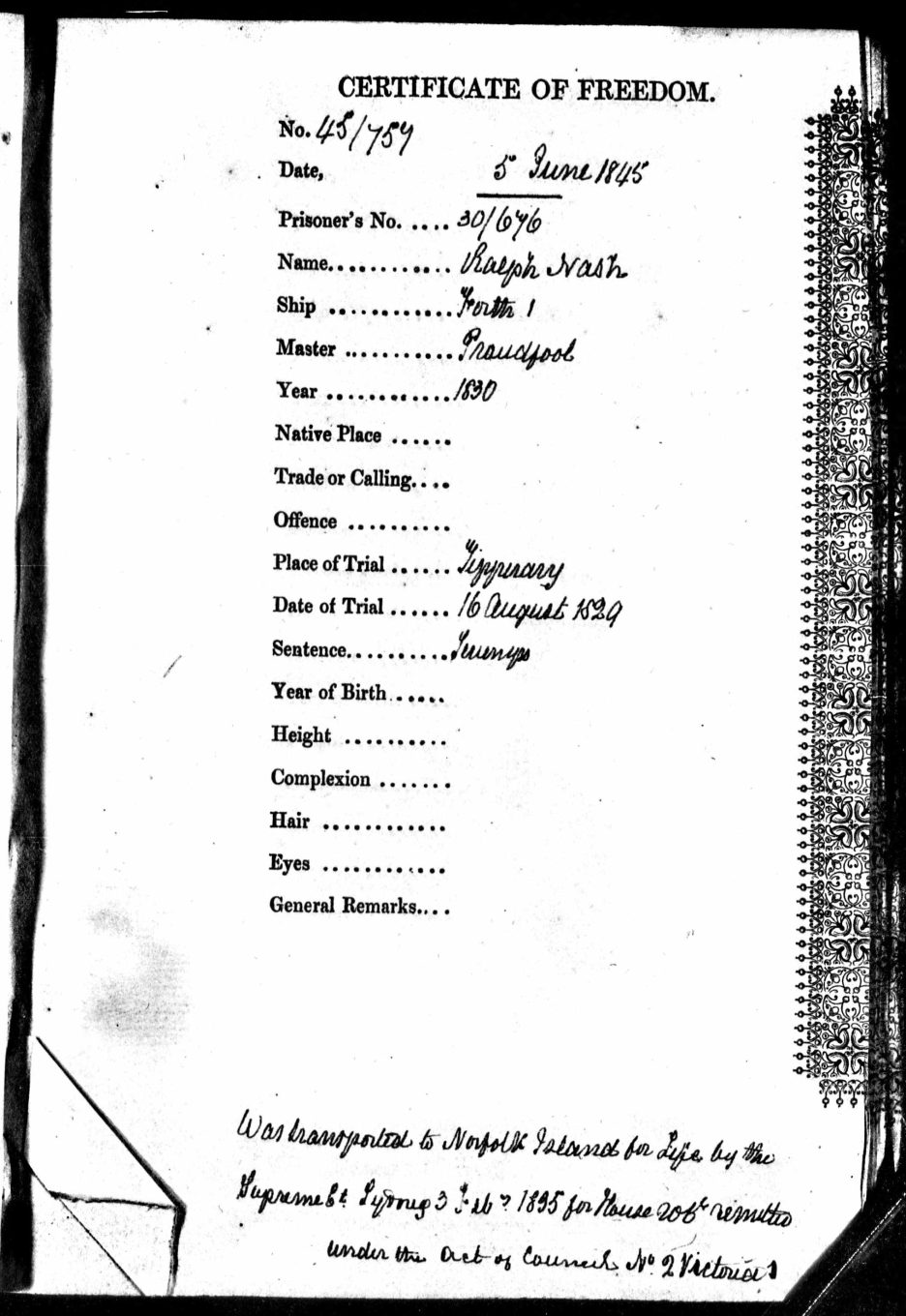

Eight years following Henry’s emancipation, Ralph was given another opportunity, not only had he been returned to Sydney Town, but he was also granted a ‘ticket of leave’. While not a release from his sentence a ticket of leave allowed Ralph to participate in normal society, finding his own employment and working for his own profit. With the same it was also his responsibility to see to his own housing, food, and clothing. It was an opportunity Ralph likely never thought possible. Then, on the 5th June 1845 Ralph was granted a Certificate of Freedom, effectively declaring his emancipation, his sentence had been served, and he was no longer a convict. Ralph must have been a model convict during the years on Norfolk and upon his return to Sydney Town to gain this great reward.

On the 17th February 1851, 40-year-old Ralph married 19-year-old Mary Ryan in a Catholic ceremony at Mulgoa, near Penrith. They made their home in Penrith area and the following year their first child, Ellen, was born. Penrith had a rich and early history of European settlement, particularly due to the rich alluvial land there which was suitable for various agricultural industries. A number of the early public buildings and estate homes are still standing today and can be enjoyed via a self-drive tour.

Evidence suggests that Ralph was truly a reformed character once he was finally given his freedom. Ralph established a profitable wheelwright shop in High Street, Penrith. In the 1850s and 60s at the height of goldrush fever, many hopefuls on the way to the gold fields at Bathurst passed through Penrith. Ralph’s business was in exactly the right location to serve the travelling community as they passed through the last of the ‘civilised’ world and ventured into the long uninhabited distances of outback New South Wales. Ralph would have made and repaired all manner of horse and hand cartwheels, and even the wheels of the humble wheelbarrow; many a gold seeker was on foot with all their worldly possessions in a wheelbarrow. Ralph would have also served the wheelwright needs of his local community as well, at that time Penrith was still a major service centre for the local agricultural industry. We don’t know how many wheelwrights there were in town, but there was a Wheelwrights Arms pub in High Street, Penrith.

There are reports from the period of Ralph being a respected man of good character, trusted and liked among the upstanding citizens and clergy of Penrith, both Catholic and Anglican. On more than one occasion he contributed to the benefit of the Catholic Church and its priests beyond his regular weekly offerings. In 1854 he even publicly contributed £1 toward the debts of St Nicholas’ Catholic Church, Penrith.

Despite having turned his life around, Ralph’s ‘passionate’ nature saw him in trouble with the law once more. Tragically, in 1854, Ralph accidentally killed an intoxicated friend who was making a ruckus on his property. Ralph initially asked the man to go quietly but the friend failed to do so and continued to cause a disturbance. Ralph appears to have eventually lost his temper and using a stick of wood (perhaps an unfinished wheel spoke) he hit the rump of the man’s horse and tapped the drunkard upon the head. Upon seeing that he had wounded the man seriously he had him brought into his home immediately, where the local doctor who happened to be present at the time dressed the wound and believed that the wounded man would be okay. Unfortunately, mere hours later the man passed away from brain injury. Ralph was evidently upset and deeply sorry for the death of his friend. In the court trial the jury were asked to consider his sorrow and his good char. er when deciding upon their sentence. Ralph was declared guilty, but the jury called for mercy in his sentencing. The judge deliberated over the sentencing but tried to comfort the heartbroken Ralph by saying his sentence would be as short as he could possibly make it and that he would not be sent away on a road gang. Ralph was sentenced to 18 months hard labour in Parramatta Gaol with the sentence to be commuted after 12 months for good behaviour. It must have been a tremendously difficult time for Ralph and Mary, not least due to the loss of their friend at his hand, but also the terror at once more being shut away with Mary due to give birth to another babe in the new year. Thankfully, Ralph’s sentence was remitted, and he was released on the 15th January 1856 after serving 13 months.

Following his release from prison Ralph returned to his home and wheelwright’s shop on High Street, Penrith. He continued, as before, a good citizen and profitable tradesman. His name appears in the newspapers of the period several times during his life, demonstrating his commitment to his community as a conscientious and civic minded man.

That same year (1856) Ralph and Mary’s first-born child, Ellen, died at 4 years of age, and back home in Ireland, Ralph’s father also passed away. Soon afterward, Ralph’s sister Catherine (Kate) and her husband, Patrick Coffey, and their family arrived in Australia as free settlers onboard the Commodore Perry; on Kate’s passenger manifest it was noted that Henry and Ralph were both at St Mary’s, South Creek (early names associated with the area of Penrith).

Ralph and Mary remained in Penrith for the rest of their lives and had 10 children together (sadly they lost another daughter, Julia, in 1865).

As his family grew Ralph took opportunities to provide for them as needed and in 1873, he won the mail delivery contract for the Penrith to Emu route. This was a horseback delivery service that ran twice a week, and the contract was for 3 years; it’s likely that one of Ralph’s sons, John or Edward, fulfilled the contract.

On the 12th May 1877, just before the 4th birthday of their youngest child, Mary passed away (was this unexpected/sudden? We need her death record), she was 45 years old. Ralph at 66 years of age was left a widower with young children to care for. News reports of the period note that their eldest surviving daughter, 20-year-old Elinor May, was of immense comfort and support, and took over her mother’s role in the household. Her duties must have been a heavy burden for the young woman and perhaps more so the following year when Ralph developed a painful cancer on his lip that spread to his neck leaving him with large open wounds.

Tragically, the next death that occurred, on the 27th March 1879, was young Elinor’s. She died suddenly from unexpected heart disease, and the loss was felt throughout the community. No doubt Ralph’s other daughters were well trained to step up and continue the household management, but the grief in the household was heavy and the uncertainty considering Ralph’s worsening condition must have been deeply felt.

On the 1st November 1879, just 7 months after the death of his daughter Elinor, Ralph finally succumbed to the cancer. He was buried alongside his beloved wife and daughter at the Sir John Jamison Catholic Cemetery, in Jamisontown, Penrith. Ralph’s eldest son appears to have taken on the responsibility of the family following Ralph’s death and no doubt Ralph’s extended family living nearby were of some comfort to the surviving children, the youngest being just 6 years old.